My mother said something close, once, to what O’Connor said to Corn.

I don’t know how old I was–maybe 11 or 12–but I know I was young enough to be nervous about what I felt I had to say to her. I’d been mulling it over in my room and finally worked up a head of steam and went downstairs, where I found her folding laundry on the dining table.

“Mum*? I don’t know if I believe in God anymore.”

I know I was young, too, from her reaction. She didn’t seem alarmed. Instead, she put down the shirt she was folding and said the last thing I expected, given the stakes we’d been led to believe attended questions of faith.

“That’s ok.”

Having doubts, she explained, was a perfectly normal part of being a Christian. Think of Thomas, who’d demanded physical proof of the resurrection before he’d believe it—not one of the Gospels’ heroes, maybe, but the kind of model you could be thankful for in moments like this. She herself had had struggles, she told me. What mattered, she told me gently, was that I had already given myself to God, and so all of these thoughts were occurring within the safe boundaries of my having been saved. God would not abandon me in my moment of uncertainty—and in the long run, my doubts would strengthen my faith rather than threaten or diminish it.

I felt a superficial relief after that—first that she wasn’t angry, or even worried; second that the crisis I’d imagined I was having was all comprehensible within the framework of belief, of the church. I was in no danger. I was grateful to my mother then, and have remained so since, fo taking a broad view, reacting to what I’d worried a was a terrible confession with enough equanimity to assure me that everything was going to be ok.

But even when I was young I think I also felt disappointment fringing my sense of relief. Perhaps I’d wanted more of a scene, more concern—I was a child who often fantasized about being at the heart of a crisis. But also: was there something in her response that didn’t take my doubt seriously? How could God stand by me in my doubt if God didn’t exist? Maybe it felt good to be reassured that my feelings were normal, but those assurances made sense only if you took as a given the very assumptions that I was questioning.

The difference in what O’Connor told Corn didn’t hit me until now—my mother’s response was similar in shape but not in substance. In O’Connor’s formulation, doubt wasn’t just a normal bump on the road of faith—it wasn’t something I should expect to see dissipate on its own, or even that I should expect to overcome. For O’Connor it sounds like doubt was an essential component of faith, another face of faith. If God were entirely knowable, what kind of God would it be? Doubt is the substance of faith. If it were not, we wouldn’t call it doubt—we’d call certainty, or ignorance. Doubt is not simply a lack of knowledge: it is an ontological condition.

A few years after Mother Theresa died, some letters she’d written came to light that gave the lie to the idea that her strength had come from her clear sense of connection with God. “Where is my Faith,” she wrote. “[E]ven deep down right in there is nothing, but emptiness & darkness–My God–how painful is this unknown pain–I have no Faith–I dare not utter the words & thoughts that crowd in my heart–& make me suffer untold agony.” There were many of them, letters in which it was revealed that she had not always felt she had access to God, had questioned every aspect of her faith, her vocation. I found these cries from the dark not only comforting but moving, even persuasive as arguments for faith—not simply in the sense of thinking “oh, if Mother Theresa had doubts then it’s ok for me to have them, too,” but in the sense that it demonstrated the inseparability of faith and doubt, that the darkness and the hope were twinned.

Faith is a struggle, my church taught. But not O’Connor’s struggle or Theresa’s struggle. In our church, the struggle was in fighting against your sinful nature or in being in conflict with the fallen world. It was a struggle against temptation, against assimilation. The existence, goodness, and accessibility of God were givens. The religion of my childhood was built around the idea that each of us can have a “personal relationship with God,” that we walked with a Jesus who was a kind of perfect friend. In my own family, God’s existence is considered indisputable because God had revealed himself personally and unambiguously to each believer in the house. My family say they could no more choose not believe in God than they could choose not to believe in the front door. A common conversion story arc in our circles included some sentence like “I wasn’t looking for God—I didn’t even want to believe. But after that, I had no choice but to believe.” If there were those of us in the family who hadn’t had those experiences, well…that was too bad, I guess.

Though it is my instinct to doubt the accounts my family give of their conversions, I try not to. They are unambiguous about having seen God’s hand intervene unmistakably in their lives, from the day he first stopped them in their tracks and said “come with me.” I have at least to consider the possibility that I have just not (yet) been called up.

It’s uncomfortable—even embarrassing— to talk about this. When I am drawn face against the glass of my religious upbringing I find myself contemplating a terrible choice: Is my family crazy? If they are not crazy, am I damned?

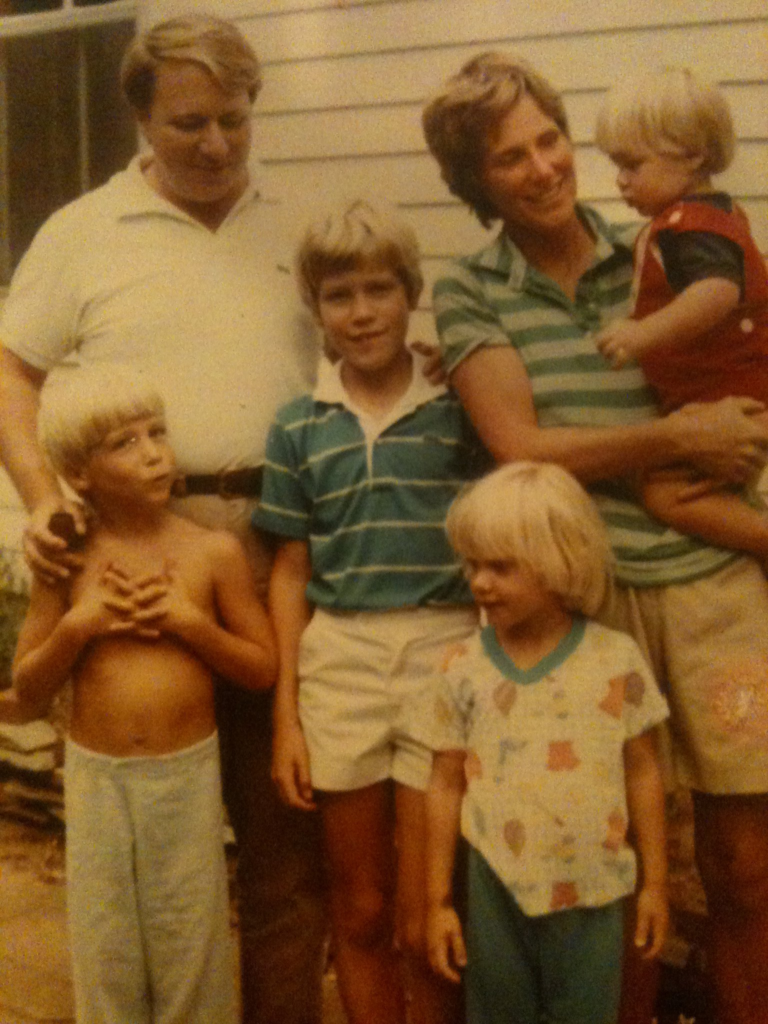

In writing these notes during Lent I am in part exploring what other options there are—what forms faith can take other than the ones my family presented me. But I love my family very much, and no small part of my drive to explore faith comes from a desire to close this last gap between us. If I were to find faith, but it weren’t one my family recognizes, will I have been glad I did?

* Long story.